Faculty Info

Name: Stacey Anderson

Academic Program: English

Average Number of students per section: 20

Featured Course:

- ENGL 102: Strategies of Successful College Writers* (two sections)

*This course focuses on helping incoming first-year students develop habits of mind and strategies for success in writing at the college-level. Students learn to make use of campus resources and academic technologies throughout the writing process. The class fulfills GE Area E (Lifelong Learning and Self-Development). Students in ENGL 102 continue with the same instructor and cohort of students into ENGL 105: Composition and Rhetoric, which fulfills GE Area A2 (Written Communication) and focuses more on research-based writing.

Had you taught online prior to the rapid shift to virtual instruction in response to COVID-19?

Yes, my first online class was in Fall 2017

What practice or technique have you implemented in your course?

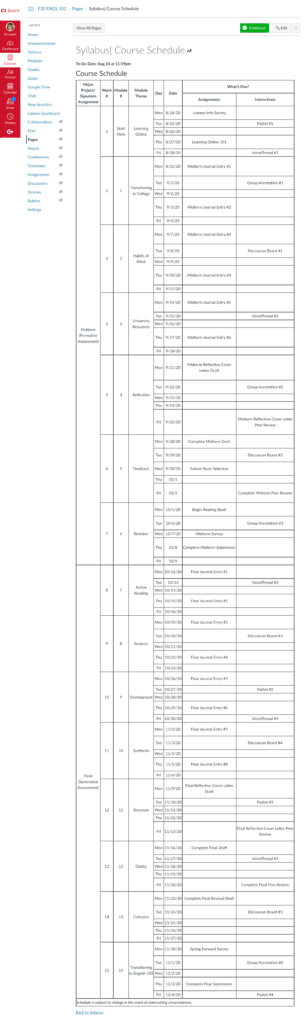

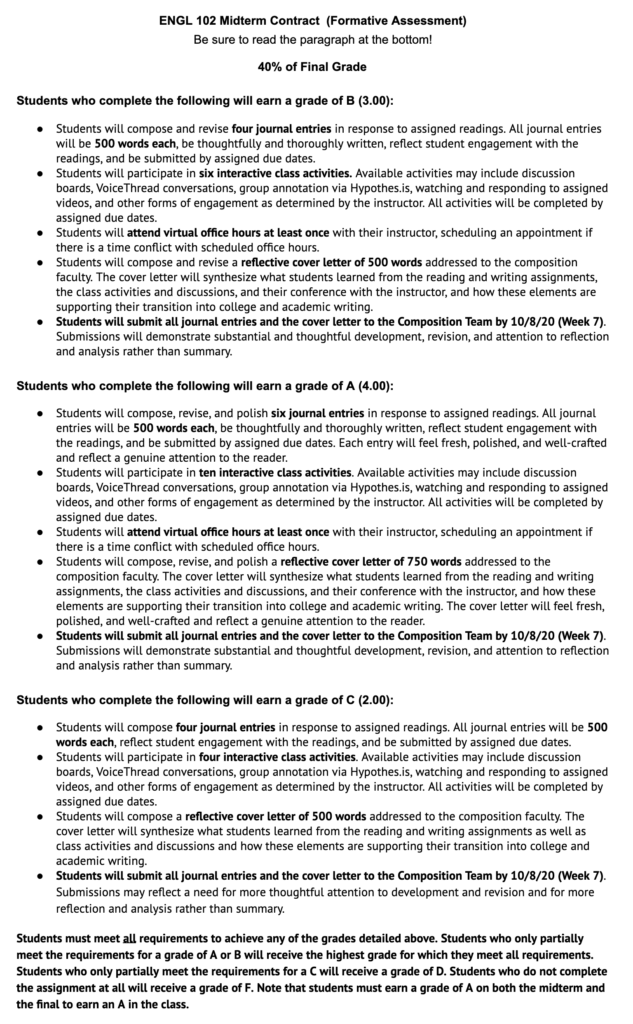

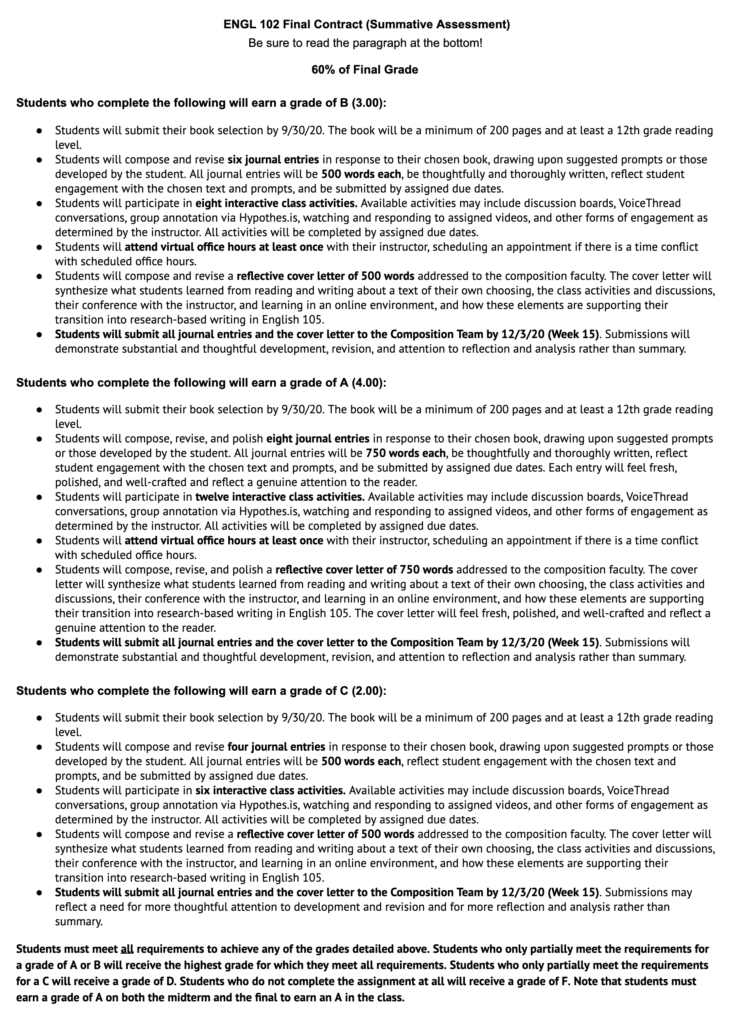

In preparation for virtual instruction in Fall 2020, our team of composition faculty designed a curriculum to keep students engaged as readers, writers, and thinkers, with a weekly schedule of assignments and activities that constitute two signature assignments. In English 102, these assignments are the Formative Assessment (or Midterm, worth 40% of the final grade) and the Summative Assessment (or Final, worth 60% of the final grade). Both the Midterm and the Final are assessed using labor-based grading contracts. Students review the contract and determine the grade they wish to target based on the number of writing assignments and interactive activities they plan to complete according to the schedule provided by the instructor.

Why did you choose this approach?

As a field, composition has been moving towards labor-based grading contracts as part of larger efforts towards culturally-sustaining pedagogies that align assessment practices with the core values of a discipline that values process at least as much as the final product. Our composition program began exploring these practices prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the shift to virtual instruction accelerated our movement in this direction. Notably, such “ungrading” practices have taken on greater traction since the pandemic, as educators across disciplines have been prompted to consider how their assessment methods align with their learning goals for students. In our composition program at CSUCI, our overarching objective is to empower students as readers, writers, researchers, and critical thinkers and to help them establish a productive and consistent reading and writing practice that will propel their success in college and beyond. Labor-based contract gradings have allowed us to prioritize this objective during a uniquely challenging time and to reaffirm our commitment to asset-based instruction and assessment.

How have students responded to this practice or technique?

Once we got past the significant learning curve of adjusting to a fully online first semester of college, students in aggregate have responded quite positively to this approach. They appreciate the clarity and transparency of contract grading and knowing where they stand based on their own accounting of their efforts. Most importantly, they are engaging with reading and writing in authentic and meaningful ways that show me they are learning, growing, and becoming more capable and confident. There are, of course, variations and struggles that are typical of any semester as well as those that are unique to this time, but the level of thinking, engagement, and improvement I am seeing on the whole has underscored the value of this approach.

Student feedback via midterm surveys also indicated that while students are eager for in-person learning, they appreciate how the class has been structured and that they have been able to succeed in this context. When asked what would enhance their experience in the class, one student wrote, “I don’t really have any suggestions, as everything has been going quite swimmingly despite the situation we find ourselves in with the pandemic.” Another stated, “I don’t have a suggestions to enhance this class. I think my experience in this class has been amazing.” This is not to say that I do not see lots of room for improvement, as I have already learned so much that will help me assess and adjust for my spring English 105 classes with these same cohorts of students.

The main suggestion for improvement I received from students in their midterm surveys was for more examples of student work. Being able to provide examples is always tricky the first time we are teaching a new curriculum, but I will absolutely be able to draw upon what students have done this semester for future classes, and I will seek out examples from my colleagues who are teaching English 105 this fall as I prepare to teach it in the spring. Students did respond quite positively to peer review (more so in fact than I normally see in face to face classes), so I am implementing more opportunities for students to share their work with each other.

Is there something you plan to change for Spring? What and why?

The primary challenge I have faced this semester is the learning curve. Some students got into the routine and understood the expectations right away, but others were struggling and they juggled multiple classes all with different schedules and assessment methods. I have already begun to implement multiple methods and modes of communicating assignments and expectations with students, with lots of repetition and re-affirmation to be sure we are all on the same page. The process of completing and submitting the Midterm/Formative Assessment was itself a learning process if not a sort of dress rehearsal, and I found myself being flexible when I realized that additional clarity was needed to make sure students knew what was expected.

A striking example came when I asked students to submit a complete draft of their Midterm. Many students, including those who had been on top of things all semester, submitted just the cover letter they were asked to write and not the journal entries. I immediately posted an announcement and a video clarifying what students should submit and extended the deadline so students could have time to pull these together. This experience helped me see the importance of clarity, repetition, and multiple modes of communication, and the value of requiring drafts. This issue was much easier to resolve than it would have been if students were submitting their final draft for grading. Process-based pedagogy is integral to composition instruction, and that is especially true in this virtual environment.

Which 3 resources and/or tools do you consider essential to effective virtual instruction?

I don’t know how anyone at CSUCI teaches without frequently visiting Teaching and Learning Innovations, but I am including that here because, as emphasized above, repetition is key. I love @ONE-the Online Network Educators, which I share with colleagues outside of CSUCI who did not have the benefit of a program like THRIVE. Anything from Jesse Stommel and Sean Michael Morris is golden in terms of digital pedagogies and inclusive teaching and assessment practices, including this new book on Critical Digital Pedagogies. And this blog post from online teaching whiz Bonni Stachowiak does one of the best things a blog post can do, which is scoping out all the good stuff and also answering a question we didn’t know we were allowed to ask. (I know this is more than three resources, but this is the whittled down version!).