Written final research papers often fill undergraduates with dread, especially if the student in question does not feel that writing is a strong suit of theirs, or they see themselves as more creative. The “unessay” – created by historian Christopher Jones – allows students to bring their own disciplinary interests and expertise to bear on historical research. For example, a student in Public health could research the history of infectious diseases and early public health efforts in the Revolutionary periods, and then create public health posters for their project. A nursing major could write a short story about someone’s first day in a hospital during the Revolution, drawing on some person’s extant writings and other primary sources. A music performance major could compose an original piece of music about Revolution and freedom. I now give my students the option between a traditional research paper and an “unessay.”

Why this might be a “fit” for your own classes: students may choose their own topics within the parameters of the course, they may present it in any way they choose, and it will be evaluated based on how compelling it is. Students must do actual research in scholarly books and articles and in primary source materials, including online databases and digital history projects relevant to their research. The idea here is to break open the corral of the traditional essay and encourage students to take a different approach to the assignment. It requires some creativity. But the results can be phenomenal!

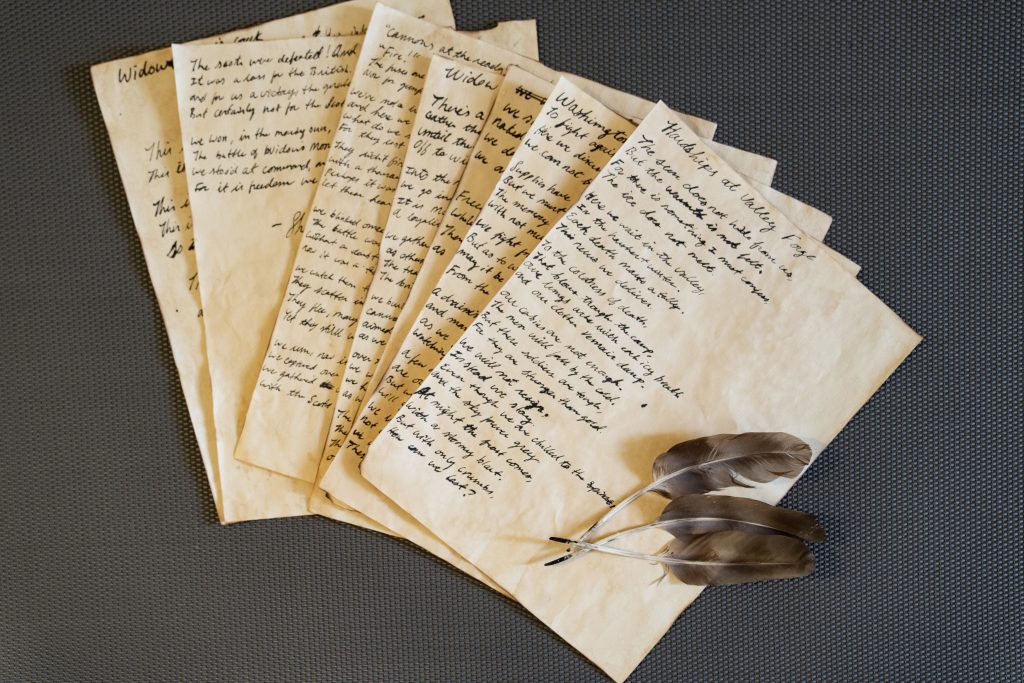

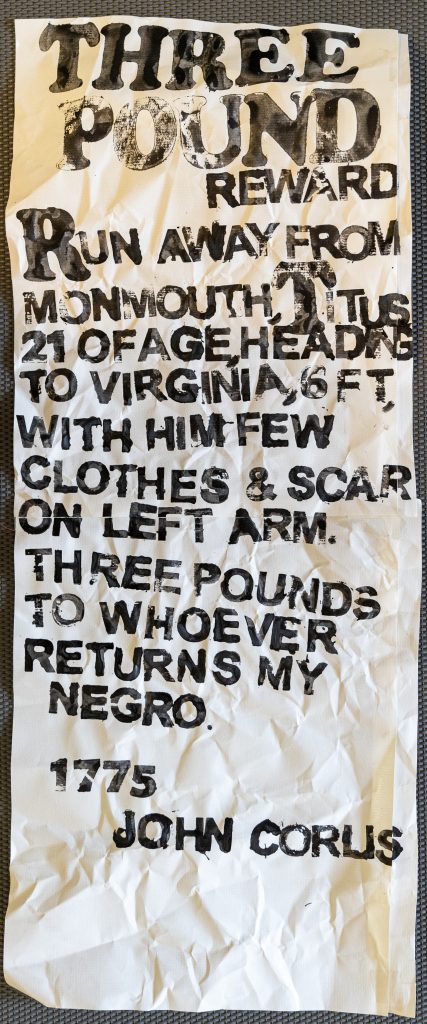

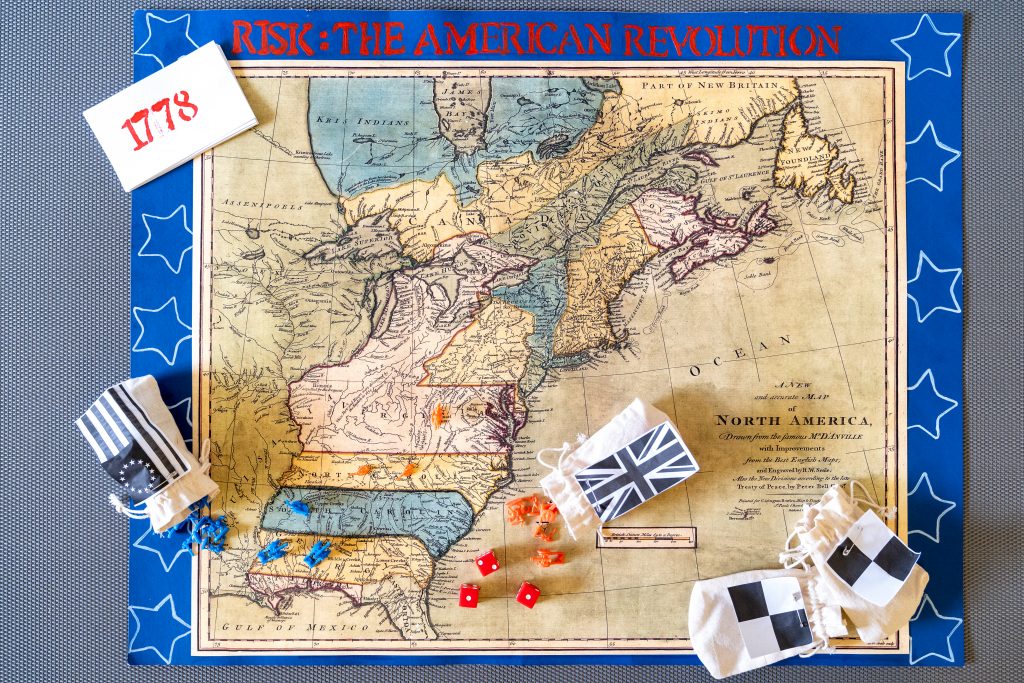

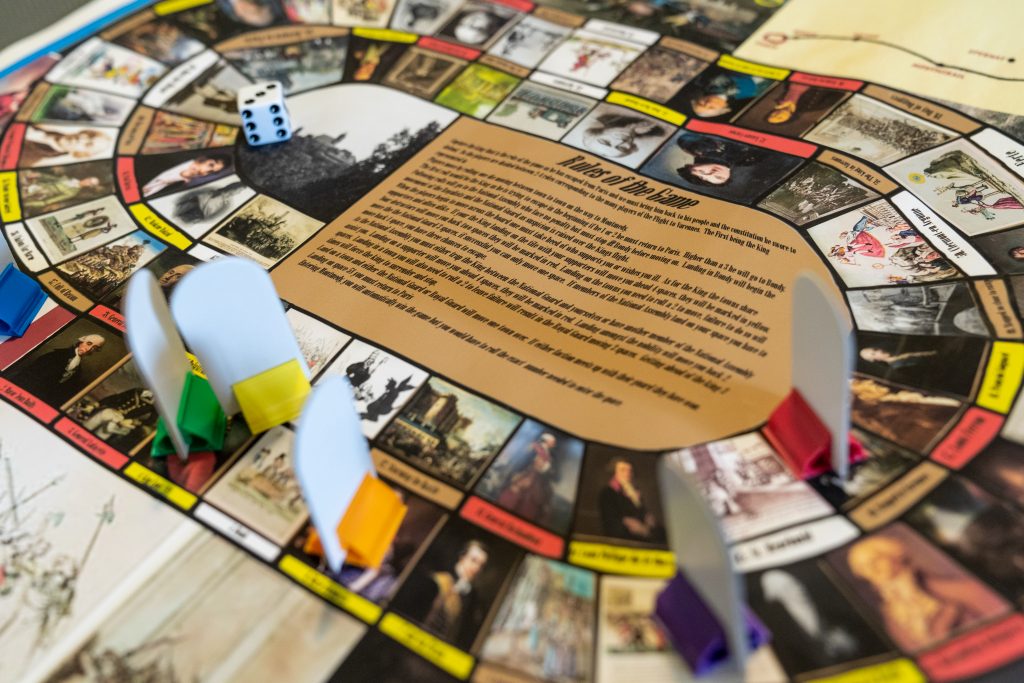

Students need to consider their strengths, talents, and skills and think about how to apply them. I gave this assignment in my Age of Revolutions History course. Several students made board games (with detailed instruction and game pieces), on subjects as diverse as the death rate of soldiers in the American Revolution, to the flight of Louis XVI to Varennes. Another recreated Revolutionary poetry and recreated two poems for recital (using a handmade quill and tea dyed paper). One student replicated the cooking techniques for prisoners of war found in an old letter during the American Revolution and brought the class the “mush” that she cooked over an open fire for three days. It wasn’t bad! An art student painted an original piece based upon the theme of “terror” in Revolution; it is haunting. Still another hand printed a runaway slavery notice based upon a printing technique in Saint Domingue during the Haitian Revolution. One student studied the letters of Olympe de Gouges and Marie-Antoinette and created letters by both of them as they awaited death by guillotine. In Dr. Jones’ class, previous students have turned in ceramics projects, paintings, 3-D and 2-D collages, drawings, original song lyrics presented as an album, a bond financing deal for a faux 501(c)(3), a video, a play, even a couple fitness routines. Others have prepared recipes. There are numerous other ways to approach the assignment.

What I discovered is that students doing the “unessay” did about 75% more research than those doing a traditional essay. I was struck by the sense of ownership to their projects and to their subjects. One student researched how many soldiers died as prisoners of war and then actually created game cards with their names on them! Another hand-made and hand-dyed a French flag using techniques from the 18th century. And they could discuss them in minute detail with the class, who were flabbergasted at the level of precision each put into their projects.

I was initially wary of offering such a project to students, thinking that this might be an easy way to cobble something together and call it a project. Several of my history colleagues at other institutions discussed this on Twitter. To a professor, every one that had given this assignment, me included, said we would offer it again. Why? Because every student I spoke with told me they had never been so proud of what they created, and they had never worked so hard on something. Most ended up with incredible amounts of knowledge that could only be accomplished by deep reading and active engagement with sources. Several of these products sit proudly in my office; I have played the games and they are clever and so much fun! Most importantly, I remain humbled and grateful for the engagement of my students in topics that might have at first been new to them. Watching someone bring their own expertise to a foreign topic means that it is no longer a rote exercise, but one imbued with real meaning. It becomes real for them and they behave accordingly. I highly recommend you give the “unessay” a try!

I love the creativity and the “digging in” the students do when given the ability to choose an innovative way to demonstrate their learning!

Exactly! It was a great reminder!

This is a really beautiful post. Thank you so much for being a creative teacher, sharing your ideas, and for including the photos! They really make an impact. This practice is an excellent example of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles too.

Thank you!